We Shall Breathe In Memphis

by Justin J. Pearson of Memphis Community Against the Pipeline (MCAP)

“People power,” I said to myself on September 9, a Monday morning, as I watched the Shelby County Commission vote on the “1500-foot setback ordinance”, as it is known. “This is what happens when Power meets People-Power, in a community they thought was powerless.”

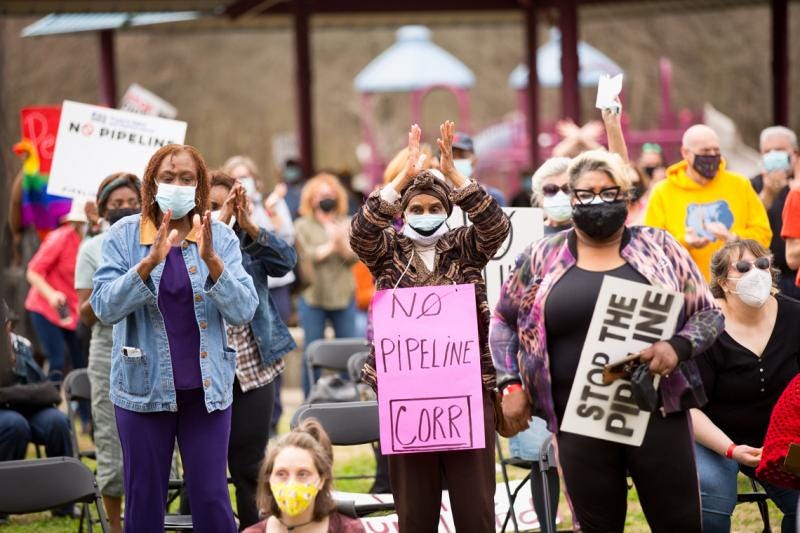

Ten in favor, two abstentions, not a single “no” – not even from the more conservative person on the commission. The result: an ordinance stating that any crude oil pipeline in Memphis must be set back 1,500 feet from homes, schools, religious institutions, and parks. Together with similar laws passed in the City Council this means, in effect, that the Byhalia Crude Oil Pipeline is dead.

The commissioners heard us. We won.

The developers had already withdrawn their pipeline in July, claiming that there was less demand for crude oil due to COVID-19. The real reason, of course, was that they had come up against unexpected resistance. They had plotted their pipeline in a zig-zig way so that it avoided the wealthier parts of town and passed through the Black neighborhoods of southwest Memphis I come from – because, as a company representative put it, this was “the path of least resistance.”

Memphis became Ground Zero of environmental racism. This is not just because of the way Byhalia was routing its line through the lands of poorer people – people it perceived would be more likely to take the money offered for access rights given they didn’t have the legal power to fight back against eminent domain. I believed we were Ground Zero because the result of this pipeline would double the productivity of the Valero Oil Refinery, which already poisons our air to such a degree that the cancer rate in southwest Memphis is four times the national average.

I grew up, like my parents and grandparents before me, in this toxic environment, the air smelling of rotten eggs. Both my grandmothers died of cancer in their sixties; two of my uncles and my older brother have severe asthma. Almost every family I know has this medical history. It’s personal for us.

And so when we heard we were considered to be “the path of least resistance,” we said “enough!” At a meeting Byhalia held to “consult” with the community in October 2020, we told them what we thought: “We don’t need a pipeline running through our land,” said my mother, Kimberly Owens-Pearson, a schoolteacher who has given her life to the community. “We need clinics and medical care to deal with the asthma and the cancer the refinery has already brought upon us.”

Given sums as little as $3,000, one hundred and sixty landowners ceded rights to their land. If they held, they were threatened by the company’s agents with “eminent domain” – an abuse of a constitutional provision usually used by the government for public projects. This would mean losing their rights anyway, with no compensation at all. Two brave Memphians – landowners in Boxtown, settled by emancipated slaves – held out: Mr. Clyde Robinson and Mrs. Scottie Fitzgerald. Byhalia had asserted the claim of eminent domain on both. When they fought back, MCAP joined them in the lawsuit. We won, and have been successful securing their land for future generations.

We rose up.

We rose to the tradition of Ida B Wells, who documented and exposed lynchings and other racial violence in her Memphis Free Speech and Searchlight newspaper over a century ago. We rose to the tradition of Memphis’ Black sanitation workers, who effectively launched this country’s environmental justice movement in March 1968, when they went on strike for better working conditions. “The Movement lives or dies in Memphis,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr said, addressing his team in Atlanta, just before he was assassinated here in Memphis.

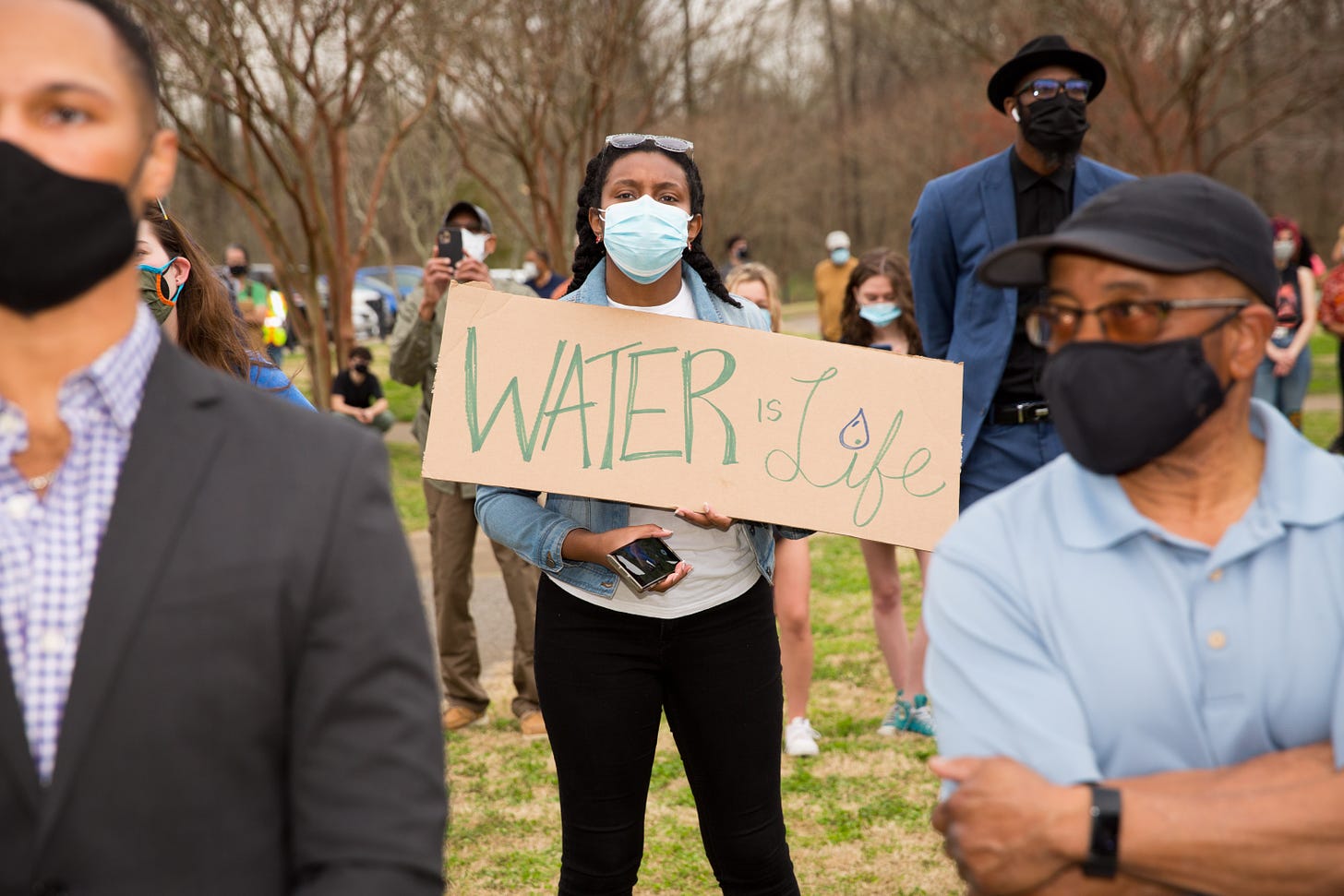

I thought of these words often, as I worked with the other founders of MCAP and our partners to mobilize our community, going door to door, holding rallies, and lobbying those in Power. The Movement lives or dies here.

There had been objections to the pipeline from the time it was proposed in 2019, backed up by science, and by powerful neighborhood associations. The pipeline was planned to pass atop the Memphis Sand Aquifer which provides Memphis with its famously clean water, putting it at risk. When we at MCAP added people-power to the data-power, people in Power took notice. Our community had been suffocating: beneath the silence of our leaders, the pollution toxins in the air from corporations, and a global pandemic amidst a global reckoning with racism.

“We Shall Breathe,” we insisted.

This was in the wake of the summer of 2020, after the lynching of George Floyd and the uprising that followed. With my whole family, I marched down Beale Street chanting “We Can’t Breathe!” Now, as I engaged for the first time with the data behind that smell of rotten eggs I had grown up with, I realized how much the fight to stop the Byhalia pipeline was a fight against a system denying us the right to breathe.

This was in the midst of the pandemic. We were learning about how COVID attacks the lungs. Many members of my own family are at higher risk because of asthma. Why did we have asthma? It was all beginning to click. In southwest Memphis – as in so many other neighborhoods of Black, brown, indigenous and poor people – we are being subject to a slow lynching, not as immediate as a police officer's shooting or a knee on the neck, but as pervasive: white supremacy being ingrained in systems that destroy and disrupt our communities. Our community has started to recognize this. “The more I learn about environmental racism, the more I believe it killed my mother,” was written on a poster at one of our marches.

As I said, it’s personal. If one aspect of this is a deepening understanding of how we are being suffocated by environmental racism, another has to do with how we are being disenfranchised, and our legacy disrespected.

Some time in the middle of it all, when it was by no means certain we would win, I paid a visit to my Great-Grandmother’s grave for the first time in my adult years. She rests in the little cemetery at the church my family has attended for over a century on Weaver Road – a quarter mile from where the pipeline would run. She was my Paw Paw’s Mama: her own parents were Mississippi sharecroppers who were themselves grand-children of enslaved people. They crossed state lines into Tennessee, and with the little they had they bought a piece of land and built a life in Southwest Memphis.

My cousin, who tends the church, walked me to the grave. As I got there, before I knew it, I’d fallen to my knees in front of her crying, praying, and thanking her. There’s a power from the spirits that keeps us persevering when things are most difficult. I thought about her growing up and living in this country where they didn't have much of anything except their little pieces of land, and maybe their house and the church they went to. In this context, Byhalia’s abuse of the principle of eminent domain and exploitation of the poverty in the community outraged me. This is our history. Our identity. Our dignity. I understood, viscerally, why Scottie Fitzgerald was not going to have that oil gushing down a pipeline over her Mother’s land, rattling her ancestor’s bones.

The significance of Scottie Fitzgerald and Clyde Robinson refusing to submit to these billion-dollar companies is personal and historical. Their land is in Boxtown, settled by emancipated enslaved people, who built their first homes with the discarded timber planks used for boxcar freight at the nearby railyard. For all of us in the neighboring communities of southwest Memphis, the devaluing of Boxtown became symbolic of the devaluing of sacred places, of our history, and of our people.

As we went door to door, speaking to neighbors on Mitchell Road and Weaver Road, in Westwood and Boxtown, we came to understand how deeply these two interconnecting issues affected people: the environmental racism of today – contaminating our air and our water – and the power of our history on this land, the power of our ancestors. Eventually folks couldn’t talk about one without talking about the other.

Making those connections was an important first step of our community association’s mobilization strategy. Then, we had to bring others in too. As I’ve said at our rallies: “We share the same sky, and pollution doesn’t have a point where it just ends. We share the same water, and it’s not as if there’s a point where it suddenly gets clean.” We had the science, and now we had to mobilize it into action: all of Memphis’s famously clean water would be threatened by the pipeline. Byhalia and its supporters were suppressing and ignoring this data. We at MCAP made it our business to amplify it. That’s what turned the corner.

We were able to engage with people and say, “look, there’s something universal here that is being impacted. It’s going to affect all of us.” The whisper from the communities that are oppressed became a clarion call for justice in our struggle against Byhalia, all across the city. Power was pushed to listen and then do something about it.

Some of us might be right on the frontline – like the communities in Southwest Memphis, or the folks I recently went to visit in North Carolina who are fighting the Mountain Valley Pipeline Southgate extension there. But the truth is, when it comes to environmental justice and climate justice, we are all on the frontline. Perhaps, if Black folk and poor folk weren’t seen as so dispensable – or if white folk and wealthy folk from Midtown had suffered like we have from asthma and cancer due to pollution – we wouldn’t have a climate crisis in the first place. The Valero Oil Refinery would have long ago been shut down, and cleaner energy solutions would have been found more quickly.

But here we are, in Memphis, together. As citizen after citizen stood up at the County Commission to address the commissioners on the urgency of the matter before them, two voices stood out for me. The first was the actor, Matt Raich, a white man, who insisted that the Commission acknowledge that south Memphis had been unfairly targeted, and thanked MCAP on behalf of all Memphians for leading the battle to keep our water and air clean.

The second was a young woman I know from Southwest Memphis. Her name is Tieranee and she is covered head to toe in beautiful tattoos, the last person you would expect to be addressing the County Commission as the representative of an environmental movement. And yet there she was, with her sheets of paper, calling out a recalcitrant commissioner and rattling off all this technical evidence about the Aquifer.

It made me very emotional. This Movement is bigger than a group of leaders. It is seeded in people themselves taking ownership of it, taking action. We will go forward. We will prevail. Our next step is fighting the environmental racism already taking our breath away – the seventeen Southwest Memphis facilities listed in the Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxic Release Inventory.

I’ve learned two important lessons from this struggle.

The first is the importance of being proximate to the daily challenges our communities face in their environments. The world is on fire and we can’t deny that; however, it’s hard to build a movement around an existential crisis. Even post-Ida, post the fires in the West, it’s not so easy to think about how to fight that. It’s much clearer to think about how to fight a company or a project that’s going to contaminate your water or your air, or take your land away from you. By connecting issues to the everyday suffering of people, our anti-pollution battles serve as a sort of gateway to mobilizing a broader climate justice movement.

The second lesson is about love. The struggle for justice is an act of love, and that is what is renewable in this whole fight, whether you win a particular battle, as we have, or lose it. It’s a love of history and of ancestors. It’s a love of community. It’s a love and appreciation of water and air, about what’s life-giving and life-sustaining about them. Our fight for “the environment” must be grounded with love, if we are to win.

I believe that we will win.